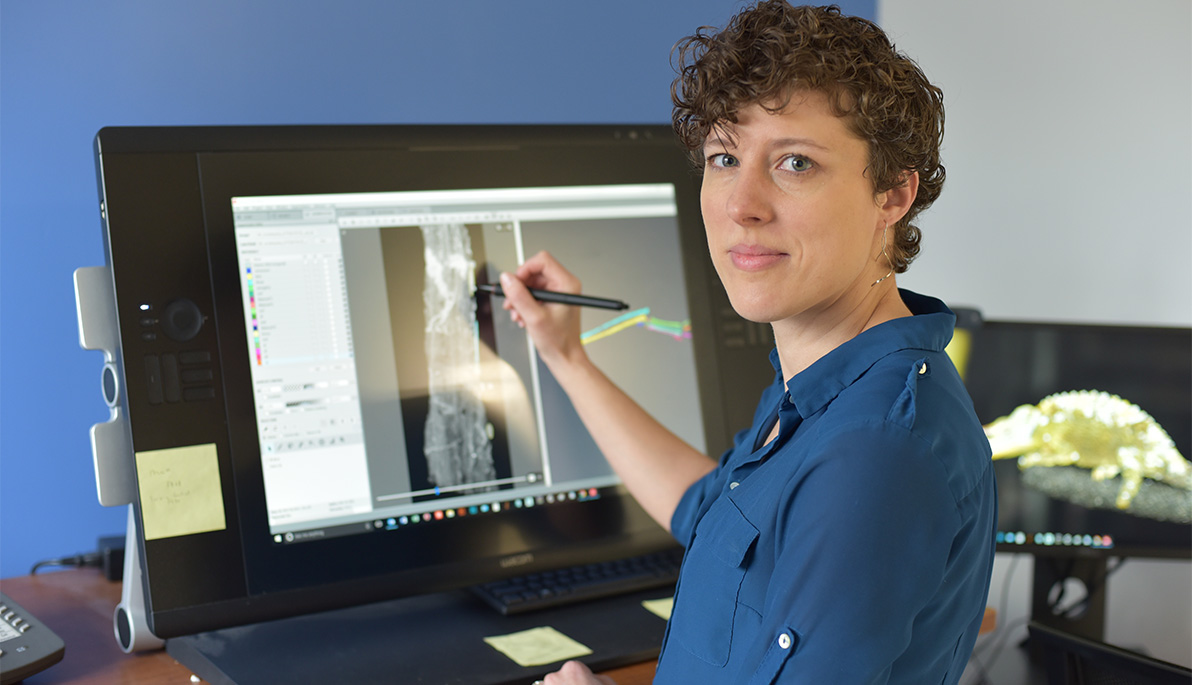

Faculty Profile: Julia Molnar

Title: Assistant Professor

Department: Anatomy

Joined NYIT: 2017

Campus: Long Island

The Art of Animal Motion

For Assistant Professor Julia Molnar, Ph.D., the road to biomedical sciences wasn’t an obvious one. The illustrator turned anatomist sat down with The Box to talk about her career journey and research on animal locomotion.

You have an interesting background. Can you tell us about it? I grew up in Knoxville, Tenn., and my path to the biological sciences was non-traditional. I received my undergraduate degree in fine arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art, and then a master’s in medical illustration from Johns Hopkins University. Then I moved to London and worked as a research technician, and I got my Ph.D. in comparative anatomy at the Royal Veterinary College.

How would you describe your research?

I study how animals move, and how their movement changes over time and in different environments. As animals explore new environments, the shapes of their bodies and how they move change in ways that can be both familiar and surprising. For example, chameleons and monkeys both live primarily in trees, and both have hands and feet that are adapted for grasping. However, while monkeys grasp branches between their fingers and thumbs, chameleons have two “super digits” on each hand and foot that are made of two to three fingers or toes held together by skin, producing a pincer-like structure. Two different animals with the same mechanical problem arrived at two anatomically different solutions.

How do you see your research being used? My research is basic science, but I hope that understanding more about vertebrate locomotion, from a comparative and evolutionary perspective, will help veterinarians and conservationists care for animals. Also, I see my work as an end in itself: The process of learning about the world around us, the creatures we share it with, and the patterns that persist over time and across species enrich us regardless of research outcomes.

What do you love about anatomy? I appreciate that in my field there’s always something new to learn. For example, right now I’m using a new technique to measure muscle architecture—like the length of muscle fibers and how they attach to tendons—using contrast-enhanced micro-CT images. This makes it possible to get detailed information about rare specimens without having to dissect them.

How do you apply this to the courses you teach? I teach anatomy to first-year medical students, but I don’t really see it as teaching so much as guiding them through an experience. A lot of anatomy departments are moving away from cadaver-based anatomy teaching towards virtual anatomy models, but I think it is important to give students the opportunity to interact with a real human body. It gives the students a chance to really connect with their first “patient” as they discover anatomical variations and pathologies and see evidence of medical treatments that the donor had during their lifetime. They are inspired by the generosity of a stranger who wanted to help them become doctors.

What can you tell us about your time at NYIT so far? My experience working with NYIT students has been very rewarding. At the moment, I’m working with one of the academic medicine scholars, Christine Chevalier. We are studying one of the most important transitions in vertebrate evolutionary history: how the leverage of limb muscles changed as vertebrates first moved onto land. My scholar from last year, Arnavi Varshney, did an amazing project on chameleon locomotion. All of the students I’ve worked with so far have impressed me with their academic abilities and their willingness to dive into a new and pretty unconventional research area.

I am also involved in a project led by two other NYIT faculty members, Assistant Professor Aleksandr Vasilyev and Assistant Professor Akinobu Watanabe, Ph.D., to create a virtual reality morphology museum. Imagine being able to minutely examine a specimen from every angle, dissect its muscles and organs, and take histological samples—right from your laptop! And it’s not just for convenience. Being able to access collections remotely will allow researchers to increase our sample sizes and broaden our comparative datasets, ultimately leading to better science.

This interview has been edited and condensed.