About Face: Why Neanderthals Look Different From Modern Humans

April 18, 2018

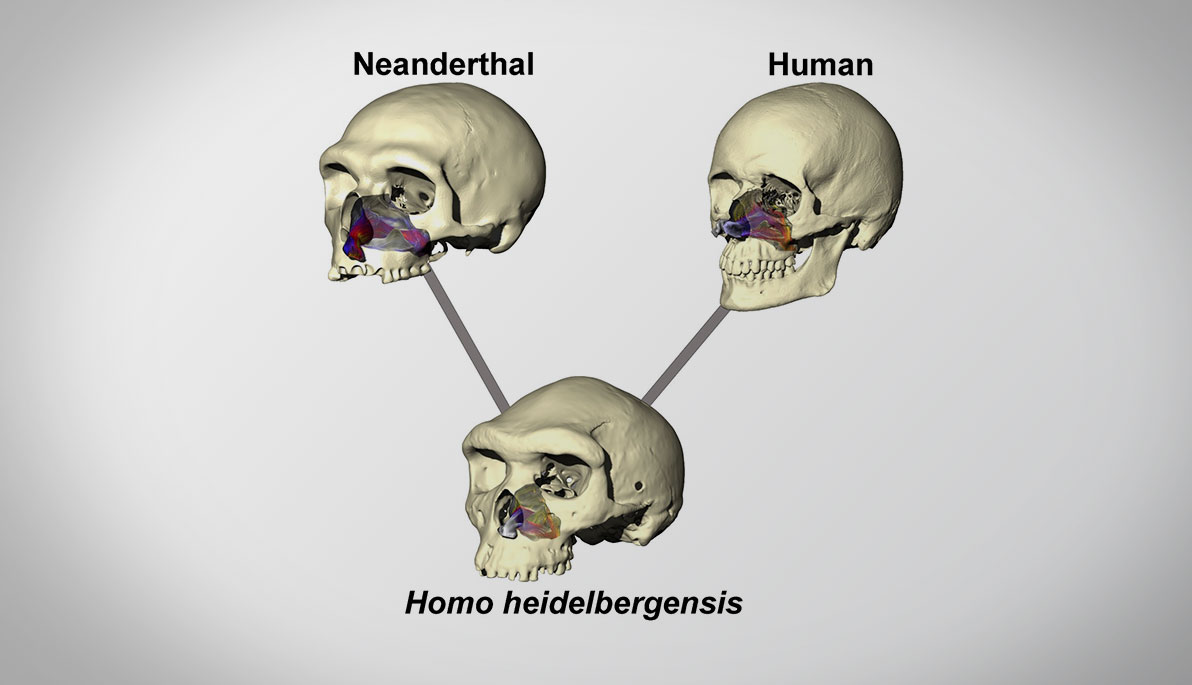

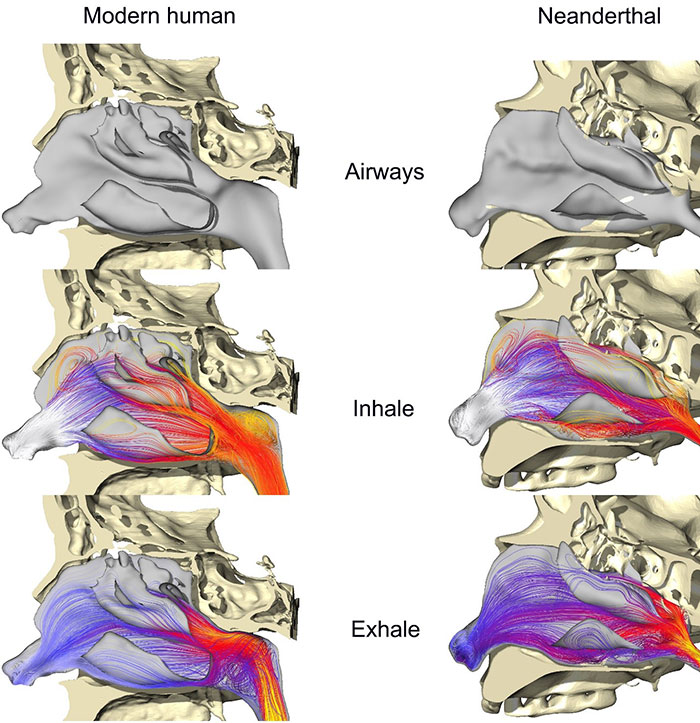

Pictured: The difference in skull and nose shape in the three human species were tested. Airflow is color-coded for temperature (warmer colors = warmer air, cooler colors = colder air). Lines indicate that Neanderthal and modern humans likely diverged from an ancestor very close to Homo heidelbergensis.

Scientists have long wondered why the physical traits of Neanderthals, the ancestors of modern humans, differ greatly from today’s man. In particular, researchers have deliberated the factors that necessitated early man’s forward-projecting face and oversized nose. Now, an international research team, which includes Assistant Professor Jason Bourke, Ph.D., (an anatomy and fluid dynamics expert at NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM) at Arkansas State University (A-State)) and is led by a professor at the University of New England in Australia, may have the answer. Their research was published in the April 4 edition of The Royal Proceedings Society B.

Recognized as the original “cavemen,” Neanderthals lived 60,000 years ago. Their fossil remains (the first fossil humans to be discovered) were originally uncovered in the early 19th century in what is now Belgium. Remnants indicated these ancestors were shorter and more robust and muscular than today’s average human. Perhaps most noticeably, Neanderthals had a much larger nose and longer face, with the mid-part of the face jutting dramatically forward.

“The physical variations between modern man and ‘cavemen’ have caused Neanderthals to be historically characterized as barbarous, dimwitted, and generally inferior to the contemporary human in almost every way,” said Bourke. “Yet, as we learn more about their diet, spiritual beliefs, and behavior, we realize that Neanderthals were likely more sophisticated than previously assumed, and aside from their facial structure, may not have been so radically different from today’s humans. Now the question begs, why did they look so different?”

To answer that question, the researchers applied sophisticated computer-based methods and simulations to compare the physiological behavior of Neanderthal to today’s human. The study is the first to include mechanical engineering simulations of Neanderthal biting, as well as the first to provide a comparative analysis of airflow and heat transfer in the nasal passages of multiple extinct human relatives.

Airflow comparison between a modern human (left) and Neanderthal (right) when breathing in air at 0°C (32°F), with warmer colors representing warmer air flow and cooler colors representing colder air flow. As demonstrated, Neanderthals were better suited to condition large amounts of cold air than today’s humans.

Three-dimensional virtual models of both Neanderthal and modern human subjects were created from Computed Tomography (CT) scans. The models then performed simulations to replicate facial responses to various everyday situations, including biting at the front teeth and inhaling cold air through the nose. In addition, the researchers simulated a more primitive early human, Homo heidelbergensis, to predict how Neanderthal’s predecessor behaved and determine the direction of evolution.

“Homo heidelbergensis provided us with an evolutionary compass,” Bourke explained. “It allowed us figure out what features Neanderthals inherited versus the novel anatomy their species evolved.”

This approached permitted the researchers to ignore the Neanderthals’ strong brow ridge (an inherited feature) and focus more on their enlarged nose, which is a unique feature of the species. Existing theories suggest that Neanderthal’s large facial structure enabled them to have a stronger bite in order to chew harder food, but the engineering tests suggested a different reason for these distinctive features. Unlike today’s humans, who breathe through a combination of the nose and mouth based on activity level, Neanderthals, it would appear, relied more on their nose for breathing—a function that would have required a more prominent mid-face.

“While our data found Neanderthals to be somewhat less efficient in conditioning air than today’s humans, they greatly outrivaled today’s humans in their ability to transport large volumes of air through the nasal passage into and out of the lungs,” said Bourke.

In fact, the research team’s simulations demonstrated that a Neanderthal’s nose was able to transport twice as much air to the lungs than a human today. That “super power” could have fueled the more strenuous and energetic lifestyle a Neanderthal required to chase and hunt large animals. The ability to condition large amounts of oxygen in colder temperatures would have also enabled Neanderthals to remain warm and active in Ice Age environments.

More Features

An Alumnus’ Commitment to the Environment

As an energy management graduate from New York Tech’s Vancouver campus, Jasdeep Gulati (M.S. ’22) is highly invested in educating people about environmental and climate sustainability.

Vancouver Faculty Win University-Sponsored Research Awards in New Program

The new Global Impact Research Grant (GIRG) program has been developed to keep Vancouver-based faculty connected to faculty and research projects being conducted on the university’s New York campuses.

Studying Climate Change One Degree at a Time

Junhua Qu (M.S. ’24) began her collegiate journey in Beijing. But, her interest in climate change took her to New York Tech’s Vancouver campus to study energy management.