Dinosaurs Chilled Out With Built-In Snout A/C

December 21, 2018

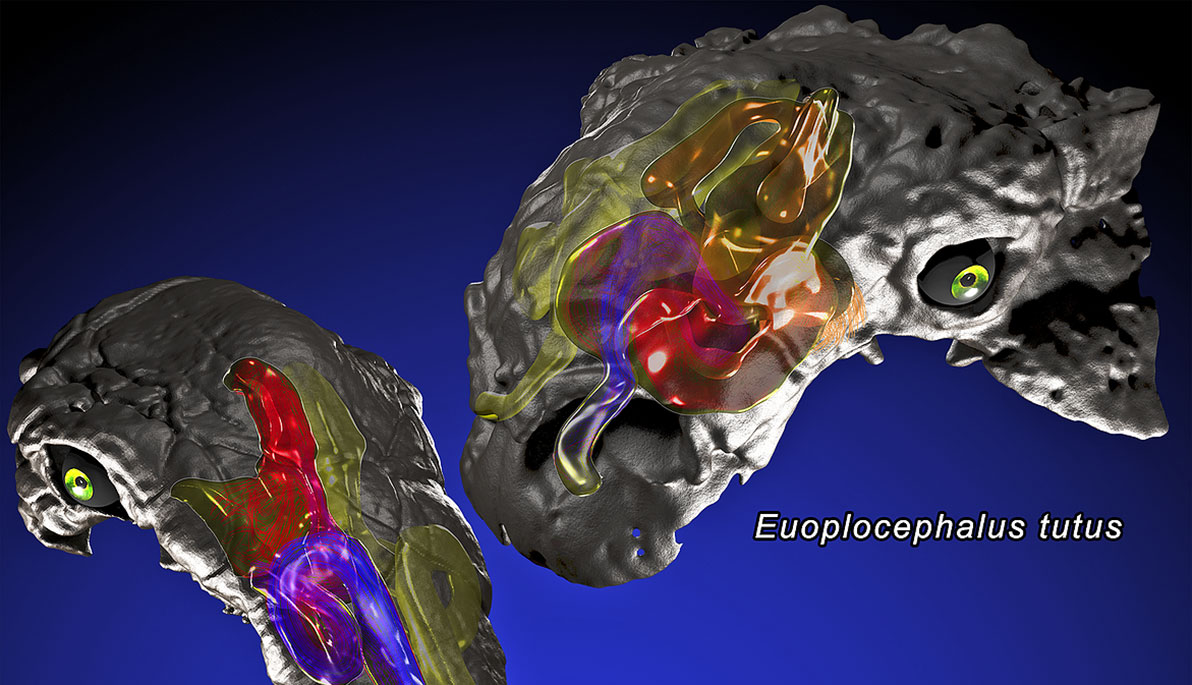

Pictured: Diagram showing the nasal workings of ankylosaur species (left) Panoplosaurus and (right) Euoplocephalus.

How did gigantic, heavily armored dinosaurs, such as the club-tailed ankylosaurs, avoid overheating in the warm Mesozoic climate? It's a question that has frustrated scientists—until now. In the December 19 issue of PLOS ONE, researchers, led by a paleontologist from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine at Arkansas State University (NYITCOM at A-State), have posed a new theory: Dinosaurs came equipped with an intricate cooling system...in their snouts.

While the dinosaurs’ large bodies were adept at retaining heat, their sheer size created a heat-shedding problem that would have put them at risk of overheating, even on cloudy days. In the absence of a protective cooling mechanism, the delicate neural tissue of their brains could be damaged by the hot blood from the core of their bodies. “The large bodies of many dinosaurs must have gotten very hot in warm Mesozoic climates, and we’d expect their brains to adapt poorly to these conditions,’” said Jason Bourke, Ph.D., assistant professor of basic sciences, NYITCOM at A-State, and lead author of the study. “With that in mind, we wanted to see if there were ways to protect the brain from ‘cooking.’ It turns out the nose may be the key, and likely housed a ‘built-in air conditioner.”

Smell may be a primary function of the nose, but according to the researchers, noses are also important heat exchangers, ensuring that air is warmed and humidified before it reaches the delicate lungs. To accomplish this effective air conditioning, birds and mammals—including humans—rely on thin curls of bone and cartilage within their nasal cavities, called turbinates, which increase the surface area and allow for air to come into greater contact with the nasal walls.

The team used Computed Tomography (CT) scanning and a powerful engineering modeling approach called computational fluid dynamics to simulate how air moved through the nasal passages of two different ankylosaur species, the hippo-sized Panoplosaurus and larger rhino-sized Euoplocephalus. These tests examined how well ankylosaur noses transferred heat from the body to the inhaled air. The researchers found that ankylosaurs lacked turbinates, and instead evolved to have longer, coiled noses. Despite this strange anatomy, these noses were just as efficient at warming and cooling respired air.

“A decade ago, my colleague and I published the discovery that ankylosaurs had extremely long nasal passages coiled up in their snouts,” said study co-author Lawrence Witmer, professor of anatomy, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. “These convoluted airways resembled a child’s ‘crazy-straw’—completely unexpected and seemingly without reason, until now.”

Read more coverage on the breakthrough discovery in the The Washington Post and on Nova at PBS.org.

More Features

An Alumnus’ Commitment to the Environment

As an energy management graduate from New York Tech’s Vancouver campus, Jasdeep Gulati (M.S. ’22) is highly invested in educating people about environmental and climate sustainability.

Vancouver Faculty Win University-Sponsored Research Awards in New Program

The new Global Impact Research Grant (GIRG) program has been developed to keep Vancouver-based faculty connected to faculty and research projects being conducted on the university’s New York campuses.

Studying Climate Change One Degree at a Time

Junhua Qu (M.S. ’24) began her collegiate journey in Beijing. But, her interest in climate change took her to New York Tech’s Vancouver campus to study energy management.